During my fieldwork at Tell Mozan, ancient Urkesh, I spent several years as part of the team excavating the AP Palace. My interest in the structure continued, and it became the topic of my dissertation and first monograph:

The volume is the final publication of the Royal Palace of Urkesh, built around 2250 BC. Besides offering a detailed architectural analysis of the structure, it deals extensively with methodology as a way to draw significant conclusions about the economy and the social setting that made its construction possible.

The analysis in chapters 2 and 6 is a major contribution to our understanding of the public buildings of ancient Urkesh, and of palaces from this region and time period. As a part of this analysis the proportion of perimeter to area was used to support typological definitions of rooms and an access analysis were used. These methods are seldom (if ever) used in the field, but show promise within the framework of architectural analysis.

A second portion of the monograph focuses on an understanding of the process of construction, combining data from the archaeological record, ethnographic parallels and textual evidence. This approach gives a deep understanding of the process of construction in general, as well as giving a series of 'algorithms' I developed from several sources (archaeological record, experimental archaeology, anthropological studies, textual sources) by which one can quantify the energy invested in the construction project. These algorithms are applicable in general to structures in stone and mudbrick, and as such can be used to define and compare the 'cost' and value of such structures in a meaningful way. This proposes an objective standard of measurement that can be used not only in archaeological, but also in an ethnographic context.

The theoretical considerations brought up in chapter 4 introduce aspects of theory which can be tied to the data presented in this study. Such a link between theory and data is fundamental, and strengthens the understanding of both. One strength of the approach lies in the direct tie between the archaeological record and a discussion of more abstract concepts such as ‘monumentality’ and ‘prestige’.

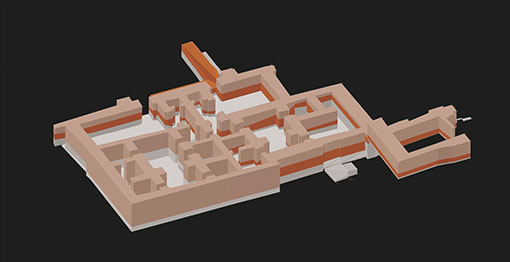

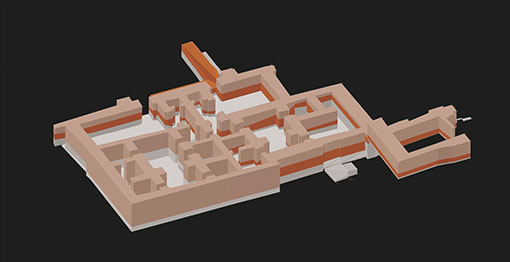

The monograph then presents a 3D model of the AP Palace at Tell Mozan, done not as an aesthetically appealing product, but as an organic research tool which can adapt to a changing archaeological reality as well as be a heuristic model. Such a model, done 'for archaeologists, by archaeologists', is a versatile tool for archaeology, and has real benefit in both formulating and answering research questions, both in the course of fieldwork as well as in secondary analyses. This 3D model is a telling example of how such a model can contribute to reaching the research goals.

The methodological approach to architectural analysis done hand in hand with ethnographic data and combined with 3D modeling techniques allows for the application of the general algorithms gained in the third chapter to the specific volumetrics of the Urkesh Palace. Such an approach allows archaeologists to better understand concepts such as the value of materials in architecture as related to studies of energetics; an approach which highlights both the individuality of this structure while placing it in a number of very interesting contexts, such as other Mesopotamian monumental structures or palaces from other cultural contexts.